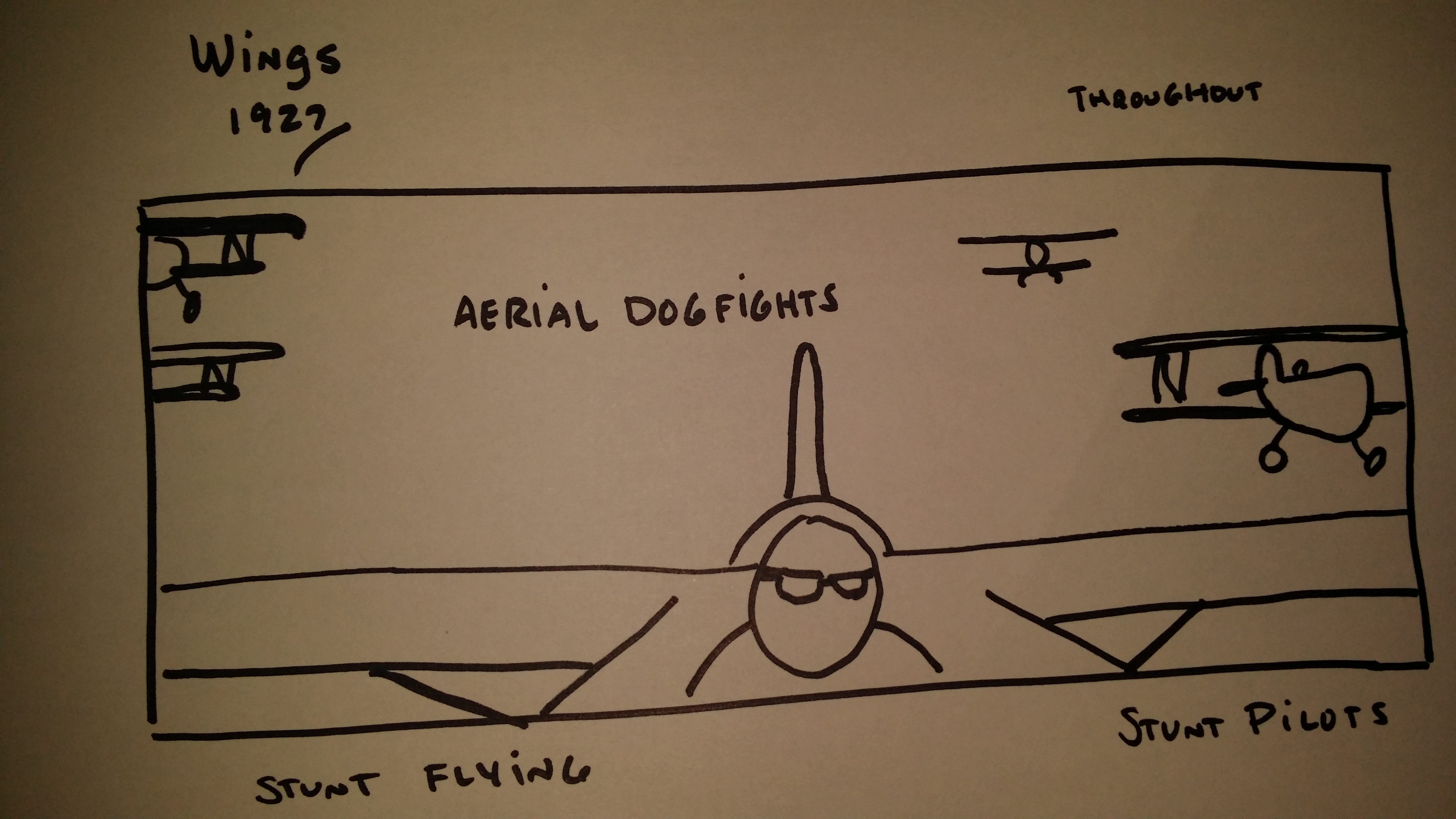

It’s important to note that the Academy Awards officially began in 1927, and the equivalent to Best Picture, Best Production, went to this film. With that in mind, I felt it important to name this movie for the Best Movie Stunts as well. The nod goes to all the stunt pilots, including Veteran stuntman Dick Grace, who was an expert at “crashing planes” and who did so for many of the crashes in this film. He even broke his neck in one of the crashes, but returned to work six weeks later to continue crashing planes. Grace was one of the few stunt pilots who died of old age. He was the author of several books including Squadron of Death, Crash Pilot, I am still alive, and Visibility Unlimited. He served in both world wars, bombing Germany, as a B-17 Flying Fortress co-pilot with the 486th Bombardment Group. After the Second World War, he operated a charter business in South America. He was married to Crystine Francis Malstrom, a stage actress who appeared in Abie’s Irish Rose.

In an article titled, “Crashing Planes For The Movie” in Modern Mechanics in July 1930, he wrote about his experiences flying for the studios, I replay it here in it’s entirety courtesy of http://blog.modernmechanix.com/crashing-planes-for-the-movie/:

“ANYONE who would crash an air-plane intentionally is crazy,” a gentleman with a florid complexion and a bulky fuselage said to another curiosity seeker by his side.

For some minutes they had been berating the foolhardiness of the pilot who was to intentionally dive an airplane into the mud flats of Sherwood Lake for the picture “Young Eagles.”

The scoffing I received at the hands of these wise men did not bother me. T5y this time I was used to it. And they were halfway right. If it were they who attempted to do such a thing undoubtedly they would be killed. I’ve been called a fool. I know many people believe me insane. The companies I work for give me no credit; to them I am but a service to be used at times when a thrill is urgently needed.

Why is it no one realizes why I consistently crawl from wreckage—from a mass of struts and torn wings which seconds before had been an airplane? Is it not possible that there is more to it than mere chance?

If I had crashed an airplane but once it could be said that it was all luck. Then I might be called a brainless fool and a daredevil. But I’ve crashed 34. If you see a squadron with that many ships on the line and say to yourself as you survey each one: “Now I’ll crash this one!” or “Here goes that one,” you would realize that 34 airplanes is quite a squadron.

I don’t mean to say that there is no danger in crashing* at a speed of from 80 to 110 miles per hour. I have had my neck, ribs, chest bone, some teeth, collar bones and a few other things broken in the last 14 years, but I challenge anyone to walk out of all of the crashes which I have done if they are performed under the same conditions and the same handicaps with which I have been confronted.

This may sound a little egotistical. To dispel any such idea I am going to expose a few of the minor details which have figured in the success of my crashes.

I have no voice in picking the location, nor can I dictate the nature of the ground into which I must fall. Sometimes it is in barbed wire entanglements of shell-pitted No-man’s Land, and at others over cliffs, or into the roof of a house, or the edge of a muddy swamp. Whatever the nature of the location, I must accept it as part of the problem I must solve. Before the stunt I must know every inch of that territory and the ground surrounding it for several hundred yards.

The next thing I note is the prevailing wind, presupposing that in all likelihood conditions on the appointed day will be normal.

One of the little details which plays a most important part in the successful completion of a thrill is the time of day at which it is done. I have always tried to crash at 11:45 a. m. Such a statement sounds absurd—ridiculous. It would almost seem as if I were superstitious. But when consideration is given to this angle it becomes quite the sensible thing to do. At that time of day the sun is highest in the skies and so there is less likelihood of being blinded as I dip a wing or tear off a landing gear.

Equally important as the sun are the general wind conditions. I have found that the best prevailing weather for my purpose occurs at high noon. There may be a slightly stronger breeze at that time than earlier in the morning or later in the afternoon, but it is usually constant and steady, varying but slightly in direction or force.

It was eleven o’clock. In three quarters of an hour I was due for another crash, so I went immediately for my physical check-up. I have made it a rule to have such an examination both before and after every crash.

The majority of people understand my object for the latter, but very few realize the importance of the former. A person’s physical condition may change enough in 24 hours to make him unfit to stunt a ship, much less crash one. For the few seconds before and during the impact every muscle and nerve must coordinate. Complete relaxation as far as feasible must prevail at such a time. If the nerves are taut, the muscles will be also. My eyes, ears, lungs and blood pressure are tested. My pulse is taken.

The minute I crawl from the cockpit of the wreck there is a similar examination. So far there has not been a difference of one heart beat. This comparison of examinations is partially a scientific experiment. It gives me a basis to analyze the reactions of crashes on my entire system. If there were a great variance it would show that I was under a strain. It would show that I had a tendency to become excited.

Again I went to the spot where the crash was to take place. The border line behind the ropes was crowded—crowded with people who, if I should be injured, might rush in and ruin the shot. To avoid such a contingency a number of my crew, who had power to stop anyone from stepping into the restricted area, were placed at intervals along the ropes.

Eight men were detailed for fire duty. They were to act at the command of their leader and his instructions were to proceed immediately if the wreck should start to burn. As equipment they had two 40-gal-lon chemical tanks and a quantity of smaller extinguishers.

The doctor and nurse stood by a fast ambulance. The motor was idling, the driver in the seat.

Now that these three important divisions were properly cared for there remained but one to receive instructions—the actual rescue squad.

In charge of this group of men was Captain Watton, a soldier and a flyer. He had been with me on “Wings,” “Lilac Time” and a score of others.

“All-set, Tom?” I asked.

“Every man has his implement of rescue as usual. One has four-foot nippers, another short steel cutters, others have hammers, saws, pliers, sledges—and as long as there is danger of landing upside down in the mud I have a pulmotor.”

I knew the captain; efficient as always. Perhaps a habit acquired from his years with the Service—maybe because he. Lieutenant Commander Harry Reynolds and I had been together so often before.

I took my last walk alone before going to the emergency field for the take-off. I stood on the spot where the ship would finally lay, and from there walked over the ground into which the ship would plunge.

Sometimes a crashing airplane will spread debris over a space of a couple of hundred feet. At others all the force must be dissipated in four or five yards, which means that the plane strikes with great impact. The speed of 85 to 110 miles an hour must be lost instantly. If the distance is 20 feet and the momentum 100 miles an hour I must stop five miles of speed in every foot of space. The force of such a shock is terrific both on the rending, tearing parts of the plane and upon the body.

The crash for which I was prepared was exceptionally difficult. I was forced to do the complete crash in approximately ten feet. The location picked for it lay in a bowl. Mountains from 500 to 700 feet completely surrounded it. Once I dropped into the uneven air currents below I had no alternative. It must be a crash, whether it was recorded by the sound cameras or not. I did not dare to miss, for directly in front of the spot, lined up on parallels, was the huge battery of cameras. An error of judgment would kill half a dozen people and injure a score more.

Getting into a waiting automobile I was taken to the ship. I felt sorry for it, all dressed up for the last flight in a newborn suit of camouflage. Rather like buying a new suit in which to bury a person. The linen was all smooth and the wings were taut. It stood there awaiting the end aloofly. But soon the linen would be crumpled, the propeller splintered, the motor pushed through its stomach and the ribs piercing its guts. It would join that ever-growing squadron of dead ships which I had sent flying out of existence so that people might gasp or cry or laugh.

Don’t tell me that ships don’t have personality. Some I like and some I hate. I hate to destroy anything I like; and like to destroy anything I hate—it’s human. And ships, of course, aren’t supposed to like or dislike, but they do perform better for some pilots than others. I think they respond, like horses, to those who really know how to handle them.

Eleven-thirty. In 15 minutes the crash was due, so I proceeded with the last of the funeral arrangements. The gas had to be drained from the main tank. Once I had a fire which burned almost 800 square inches of skin from me. No death is more horrible, more painful. To avoid this menace I built a tank on the top wing designed to carry just twenty minutes more gas than I actually needed for the flight. There are many advantages to such a system. If I used a partially full main tank the explosion would be enough to give me wings all of my own. One that is full will burn but seldom explode, there being no room for expansion of gases. It also gets away from pressure feed, though few ships of the present day are so equipped.

After draining the big tank I slit the bottom of it so there could be no sudden compression of air. I carefully measured the amount of petrol for the flight and having warmed the motor before, was set to go on as soon as the prop was turned over.

With this last precaution behind me I got into the seat. The switch and throttle had been moved so close together that I could operate them with three fingers. The tachometer was imbedded in horsehair at the left of my feet and the rest of the instruments were hidden behind a thick padding which covered the entire panel.

Other than these precautions the cockpit was similar to that of any ship, though in some with wooden or old steel longerons, bracing is often necessary.

The clothes which I wore were regulation Bedford cords, the usual leather coat, golf sox and ordinary shoes. Boots are too awkward to remove in case of leg injury. The helmet was of hard leather and the goggles the same type generally found in use today. % I have been asked many times why I don’t pad myself; why I don’t use a steel jacket or other protection. If I were looking for protection I probably would never have started crashing airplanes. Another and more reasonable explanation for such action is that if I follow my mathematical calculations to a logical conclusion, only the parts of the ship will go that I desire. Sometimes it is necessary to cut struts or to strengthen them to get the desired effect and to produce the proper dissipation of forces. If I missed, no matter what form of padding or armor I wore it would be no more protection than paper. In one of my crashes a splinter of wood pierced a steel longeron, after having passed between the belt and sleeve of my leather coat. What use then of armor? It is better to try to keep wreckage from puncturing a vital part of my body. It only takes a gash an inch and a half in the back, and then, of course, I’ll fly over to the Other Side. Until that time I can still say I’ve solved crashes.

I fastened the belt around my knees and the extra one around my chest. The latter is an invention of Harry Reynolds’ and mine. After I broke my neck on “Wings” we decided that a device ought to be made to eliminate the snap of the neck. So the chest belt. At first we built it as strong as possible, but after I had injured several ribs from the mere pressure of my chest against the six-inch webbing, we decided that it had to give just before it crushed me. We approximated the pressure necessary to break these bones at 600 pounds, providing that the speed was about ninety miles per hour. Therefore belts now give at that point.

We also found after several more crashes that even the chest and lap belts were insufficient. If I landed on my back with great force there was a tendency for me to dive out. I never quite made the final getaway, but I have bumped my head. So we put shoulder straps on the chest belt and now think that that minor detail is completely-solved.

I looked at my watch. In just seven minutes I was due. Soon as the motor was turned over and revved up it would be time for the take-off.

I adjusted the goggles and found the point on the strap which was easiest to grasp when I wanted to throw them away. Everyone knows that it would be foolish to crash with goggles on the eyes. Just a splinter of glass or a sudden gouge on the sharp steel rim and the crash pilot might never see again.

Thy prop was revolving slowly, mv goggles were in place, the blocks removed. I was down the runway with full gun on. The ship became lighter on its wheels. It left the ground—its last take-off. The motor was humming, the wires singing. Now the ship and I were one. It assumed part of my personality and I became an integral part of it. Together we had a mission to perform; a mission of mechanics and mathematics which should destroy it and leave me unscathed.

As I gained altitude I noticed that the wind was favorable. It was blowing five miles an hour, in a direction which would almost head us into it for the crash. Conditions seemed ideal.

In five minutes I had sufficient altitude to skim the mountains and with full gun on pulled over the cliffs and dropped to the gully-like bowl below. The stunt was on. I couldn’t have changed my mind if I had wanted to, and no one was more anxious to see me start into that grinding, rending spill than I was.

Those on the ground were excited. Yet under the circumstances they maintained exceptional self-control. I could see the police, fire and rescue crews standing by. I glimpsed Reynolds and Director William Wellman by the pulmotor.

But as I nosed down I paid little attention to them. I had to hit the spot, to miss cameramen and to vindicate myself by getting the effect the company wanted for the picture.

I felt a change in the air. From the smooth, undisturbed currents I had encountered above the rim of the pocket, the air became a swirling, bumpy, unsupporting mass of atmosphere. I had to have full motor to keep altitude.

Then came an unexpected bad break. As I made a vertical bank to come directly into the crash the wind switched from a breeze on my nose to a brisk 15-mile current on my tail.

That meant I could not crash at less than a hundred. I could not climb out. It had to be done. It was a rotten break of luck.

A few hundred feet ahead of me and down I glimpsed the spot. The troupe, the cameras, the onlookers might as well not have been there. I was oblivious to everything but the one spot. The finger of my air speed indicator wavered unsteadily around 105. It was going to be one of the fastest crashes I had ever attempted. Only twice before had I exceeded this speed. The one at 110 broke my neck; the one at 135 hurled me 40 feet from the ship.

At such times there are but two things to guard against; over-confidence, which makes the pilot inclined to be careless about details; and a lack of confidence, which robs his brain of the power to act decisively at the right moment. I have never been overconfident, but as I enter the last rushed moments of a crash I have supreme belief in my ability to walk out. Ships must go where I say and when I say; I could not let this be an exception.

When 500 feet away I ripped the goggles off. Then, leaning over the side of the cockpit, with the left hand on the stick and the right handling the throttle and switch, I got the last glimpse.

The ground was passing so fast that I could distinguish nothing. Even the spot was but a blurred outline in advance. The moment came. One short fraction of a second would carry me yards beyond the mark, into those cameras, the men—into tragedy.

Pushing the throttle full on I jabbed the stick entirely over to the right, dipping the wing. Just before I hit I kicked the rudder to the left, sliding the wing in first, thus keeping the motor from hitting directly on its nose.

The right wings hit and were torn from the fuselage. As the ship pivoted the propeller bit into the ground. The motor went into the main tank. Then I cut the switch. I saw the wheels tear through the lower wing toward the cockpit as the fuselage crumpled over on its back. I was upside down now. The crash was over. My face was covered with mud. Directly beneath me was a pile of scrambled iron, struts, braces and parts of the steel engine mount.

The force with which I hit was sufficient to tear one of my feet from a shoe—also to knock the wind from me and break a rib on my right side. But what a shot! I had ended just four feet from a microphone and six feet from the nearest cameraman.

The majority of people who were there did not know that in dipping the right wing first there was a motive. A broken rib on the left could puncture the heart, and that organ must be protected. Shock alone could injure or stop it altogether. The stomach, too, is farther toward the left than to the right. As I eat nothing 24 hours before a crash there is little to fear from rupture of the digestive tracts. If they were punctured it would be better not to have them filled with food.

I walked over and had my physical. There was no change of heart beats.

That was the thirty-fourth airplane which I crashed. I have still four more to do this year.

If one little strut should go wrong and play me a dirty trick should people say, “See, I told you it was all luck”?

I’ve crashed Spads, Fokkers, Jennies. I’ve smacked Standards, T.M. Scouts, and L.W.F.’s. I’ve pushed in S.E.5’s and Thunderbirds; American Eagles, Waco’s, Eagle-rocks, Ryans. Each has its peculiarities. Some must be strengthened, others weakened.

Directors have told me to slip, spin and nose into the ground. They’ve had me fly into cliffs, buildings and church-steeples. I’ve had to hit and slide backwards and have been told that the shot would be useless unless I turned the plane on its back. Once I was warned that if the ship did overturn I would not be paid, which was not easy with the wind on my tail. So I welded a heavy anvil in the rear section of the fuselage. When I hit, the plane did a complete barrel roll on the crankshaft and for seventy-five feet flew in a reverse direction. The anvil alone was responsible for the success of that stunt.

Is it all luck or isn’t there just a little bit of science to it? Some people call them scientific crack-ups. Some think me a fool. The majority who have seen me do it over and over think nothing. They expect me to get results and to walk out. But even they are so excited that they can’t intelligently agree as to what exactly happened. Some day I may gratify the pessimists and those who would like to have vindication for the statements they have made. Some day I may miss, but I don’t expect to. I don’t look forward to it. One of the worst crashes I ever had was when I slipped on wet pavement and landed on top of my mother’s Christmas present—a cut-glass pitcher.

Crashes are crashes — there are many things tougher. They’re not all fun but they’re not all hazard. The satisfaction I get afterwards compensates me sufficiently for any little inconvenience to which I may be subjected. The gasps I’ve given movie fans never will equal the drama of the moment for those on the troupe.

The reward I receive is not financial. I am happy to vindicate my judgment by doing these things scientifically. I have turned destructiveness to a constructive channel, and reduced immediate accident to artful design. There is much to be learned from crashes. I’ve learned as I’ve done them, for I get the double reaction of being in the ship and then later of seeing on the screen how they look to those standing by.

When I can solve necessary crashes, when I can teach others the results of my experiments, then I will have accomplished my purpose. Until then I shall continue to crash for your pleasure. I’ll be a double who tries to make thrilling pictures more thrilling—giving heros more heroics and hero-worshippers more to worship.”

Wings was directed by William Wellman for Paramount Productions. Director William A. Wellman had his cinematographer Harry Perry lash his cameras to the stunt planes to capture the vertiginous feelings of being in dogfights. Harry Perry would go on to win the Academy Award for Best Cinematography for Hell’s Angels 3 years later. The Battle of St Mihiel was meticulously staged, with William A. Wellman spending 10 days choreographing and rehearsing 60 planes and 3,500 extras.

Things to look up (click on item to go to IMDB page or Website):

Stunt Pilots:

Frank Andrews

Pierce L. Butler

Frank Clarke

Hal George

Dick Grace

Clarence Irvine

Denis Kavanagh

Earle E. Partridge

Earl H. Robinson

Rod Rogers

Sterling R. Stribling

Bill Taylor

Frank Tomick

Hoyt Vandenberg

Glossary of stunt terms as defined by Wikipedia:

- Aerobatics – is the practice of flying maneuvers involving aircraft attitudes that are not used in normal flight. Aerobatics are performed in airplanes and gliders for training, recreation, entertainment and sport. Some helicopters, such as the MBB Bo 105, are capable of limited aerobatic maneuvers, and Chuck Aaron is the only US pilot certified to do helicopter aerobatics. The term is sometimes referred to as acrobatics, especially when translated.Most aerobatic maneuvers involve rotation of the aircraft about its longitudinal (roll) axis or lateral (pitch) axis. Other maneuvers, such as a spin, displace the aircraft about its vertical (yaw) axis. Maneuvers are often combined to form a complete aerobatic sequence for entertainment or competition.Aerobatic flying requires a broader set of piloting skills and exposes the aircraft to greater structural stress than for normal flight. In some countries, the pilot must wear a parachute when performing aerobatics.

Check out our new Book, 100 Years of the Best Movie Stunts!