The following article is written by Jim Tully and first appeared in The New Movie Magazine in August 1931.

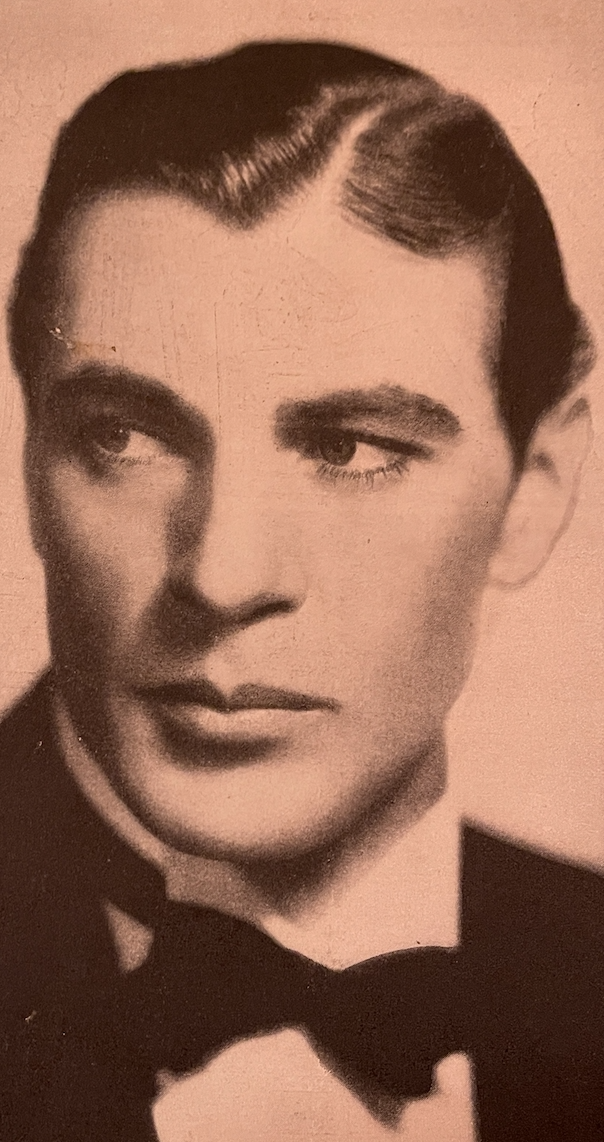

He is quiet, well mannered, and good looking, the long awaited answer to the prayers of maidens and moving picture producers– a Zane Grey hero come to life. He is natural, without pose. Vaulted suddenly into the saddle of success, he rides as easily as if he were on an aged mustang–or in his twenty-thousand-dollar automobile.

He is tolerant and kindly toward others, and honest as concerns himself.

An inarticulate fellow, there is more in him than the maidens surmise. Success may spoil him in time. Lanky, slow moving, shy, he is, at present, as clean as the wind over the Montana fields.

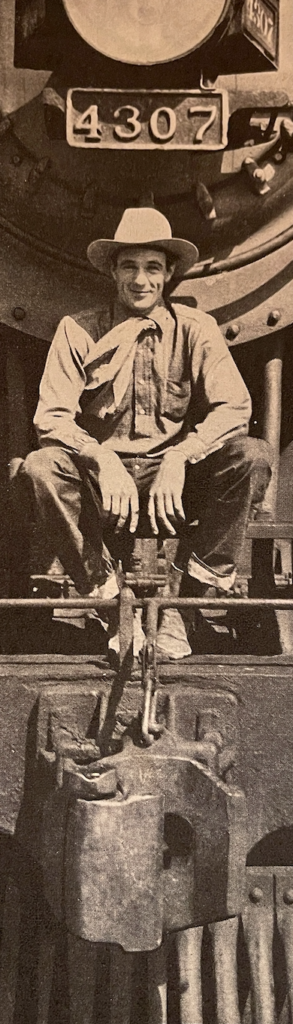

He was born in Helena, Montana, the son of a State Supreme Court Judge. At nine years of age he was taken to England, where he went to school for three years. At thirteen he was injured and sent for repairs to his father’s cattle ranch in Montana.

He went to college at Grinnell, Iowa, for two years. Returning to Helena from college, he remained for seven years trying to be a newspaper cartoonist. In 1924, he came to Los Angeles, his sketchbook with him. Failing to get a job on a newspaper, he sold space for an advertising firm. Down and out, and in desperation, he heard of a moving picture company who wanted men to “ride horses.” He got a job as (an) extra.

For a year he was a member of the vast horde in Hollywood who talk much and eat little. Then a foreign gentleman by the name of Hans Tiesler, an independent producer, hired him to play opposite Eileen Sedgwick in a two-reeler.

For his work in the film he received little money and less glory. But all unknowing, the lanky boy was riding down a well-paved road.

Samuel Goldwyn, who can see a dollar further away than George Bernard Shaw, thought that Gary Cooper might be convincing–and cheap–for a nice part in “The Winning of Barbara Worth.” He already had two stars– Ronald Colman and Vilma Banky– another well known name might conflict with them.

Thirteen months after his entrance in pictures, Mr. Goldwyn signed him to play the part of Abe Lee in “The Winning of Barbara Worth.” Mr Goldwyn was very kind to him. He realized that he was very young, and that too much salary at once might prove a temptation beyond the will power of a lone young cowboy. So he gave him fifty dollars a week, the salary a carpenter can earn, to play opposite his stars.

Cooper did not know what it was all about. The reputations of Banky and Colman and the deft politics on the set scared him.

So he did the only thing he could do–acted natural. When it came time to release the picture, it was found that gary had part of it in his pocket. Now it is known in Hollywood that not even an actor can steal anything from Samuel Goldwyn.

A gentleman approached Mr. Cooper, who was broke, as usual. He inferred that Mr. Cooper might be able to sign a contract with Mr. Goldwyn at a small, a very, very small salary. Mr. Cooper approached Mr. Goldwyn.

The last named gentleman seemed to have a change of heart. He was as cold as the editor of a popular magazine toward an honest writer.

Mr. Cooper was discouraged and willing to sign at fifty dollars a week. Mr. Goldwyn dallied–why–only an Einstein can guess.

Cooper’s part in the film was actor-proof. But that was nothing unusual. Every part in which he has appeared since has been actor-proof. The producers know that the women know the kind of ham they like.

Then B. P. Schulberg got a tip. A tall gawky boy by the name of Cooper had part of a film in his pocket. He was willing to return it to the Goldwyn, Colman, Banky outfit. They were evidently willing to accept it. But if they did, the public and the box office would suffer. And Mr. Goldwyn knows his public and loves his box office.

Cooper was allowed to keep what he had. Although, it is said, that the film cutters work diligently. Mr. Schulberg sent for Mr. Cooper. The unconscious purloiner of film was ushered into Mr. Schulberg’s office in which sat a group of men who could see a dollar even further away than Mr. Shaw or Mr. Goldwyn–that is–even in the canyon moon.

Cooper signed a contract with Paramount–Without a Camera Test.

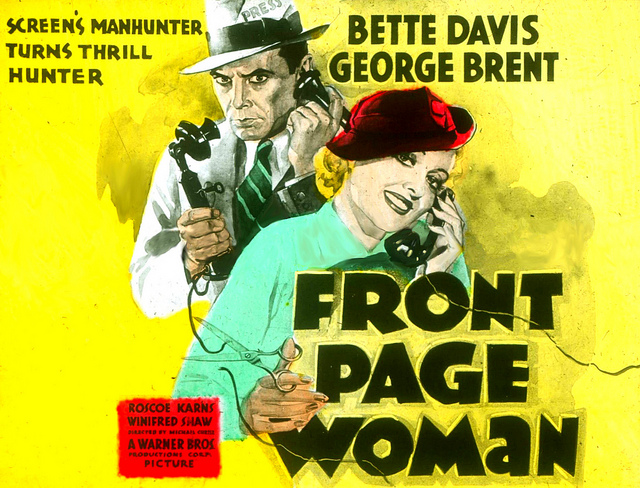

His first film was “Wings.”

It was followed by “Children of Divorce,” “Legion of the Condemned,” several Westerns and other types. Then “The Virginian.” “The Spoilers,” “Morocco,” and “Fighting Caravans.”

The rest is financial history–for Paramount. It was one of the shrewdest moves ever made by a film executive. It probably is one of the reasons why Schulberg receives eight thousand dollars a week even in rainy weather.

Cooper, one of the greatest drawing cards in the film world, receives a salary of fifty-two thousand dollars a year. It is, so I have been told, an excellent stipend. A repetition of an ancient Hollywood conflict enters.

The lanky lad from Montana is well aware that he is a far greater drawing card than many players who receive three and four thousand dollars a week. Then why cannot he get his share of what he draws at the box office?

The Paramount officials have their side of the question. In a materialistic world sagacity must receive its due reward. They gave Cooper his chance.

Cooper’s contract has two years to run. He is not happy.

Schulberg is a humane man. His sagacity is tempered with justice.

We will watch the result.

It is said that women remain loyal to tall men. The lanky cowboy will need them in two years.

In the meantime, Cooper is learning the few things he needs to know.

He knows how to capitalize facial immobility. With a minimum of expression, he interprets many moods and characters.

His eyes, heavily-lidded and well modeled, are a joy to women. His mouth, surprisingly mobile, can curve into the most infectious humor.

Quite virile, there are evidences of delicacy about him. His hands, extremely large, have beauty of contour and proportion. They are not the hands of a cowboy.

A splendid horseman, he has been cast in a succession of pictures giving him little opportunity for the display of other ability. He has none of the healthy swaggering obviousness long considered essential for a hero of the great open spaces.

He has no rating as an actor. But still, by striding across a room he can suggest diffidence, fear, and anger with greater dramatic effect than many other gentlemen hams. Directors realize this fact. His films are filled with scenes displaying his entire figure. His is the most come-hither-maiden walk in motion pictures.

He is the embodiment of that feminine ideal–”the strong silent man.” His fight scene, in the early part of “The Spoilers” was a delight. Without knowing the identity of his opponent or the worthiness of his cause, he threw himself into a brawl merely for the physical stimulation of the combat. With feet planted far apart, he delivered blow after blow with the regularity and force of one who knew how to fight. Later in the picture he engages in another fight, this time unaided, with the villain of the story. It is one of the best known descriptions of fistic encounter in popular fiction. Audiences shouted aloud in triumph as he stood, blood-stained and tattered, above the body of his defeated opponent. During the fight a lamp was broken, and much of the action took place in a dimly lighted room.

In “The Spoilers” he contributed a scene of great poignancy and strength to screen history. He stands above the dead body of his best friend. Gathering the man into his arms, he walks in silence from the group of onlookers. At the door he meets the woman he loves. He believes her responsible for the murder. Their eyes meet. He goes, still in the silence, into the Alaskan night, carrying his dead comrade. By not acting at all, he endowed this sentimental scene with the elements of high tragedy.

There was a scene of similar pathos in “The Virginian.” His best friend is captured in a raid upon cattle thieves. A member of the posse, Cooper is forced to watch the boy’s execution. Imbued with the uncompromising standard of frontier justice, he witnesses the lynching in silence. As the posse rides homeward, the camera is trained upon Cooper’s face. Without the movement of a muscle, he registered the impression of heartbreak.

He is often given shyness to portray. He is a master at the suggestion of deferential embarrassment in the presence of the other sex. The ladies love shy men–who are not too shy.

His romance with Lupe Velez has been widely publicized.

People interested in such things claim they have been married for a year.

I went with him for dinner to the home of his sweetheart.

There never was a greater contrast in two people since marriages were made in heaven.

In a simple living room, the only room in the house which does not bear the extravagant stamp of the interior decorator, he talked of Montana, where flaming sunsets leave glowing streaks in the sky late into the night, and where the trees are long etched in twilight. He was sad because people missed the shadows on the rocks which changed color as the sun moved lower in the sky.

“I haven’t read a half dozen books in my Life, “ he said, “and I’m kind of afraid of you, Jim.”

“You don’t have to be,” I answered, “so long as you’re yourself.”

The heart of Lupe Velez is not in the great prairie country. Hollywood offers all she desires–money and Gary. She is not without a metallic wisdom. Without money, in Lupe’s opinion, one has no place in the world. People are cruel to one who is down. With money, the world lies at your feet. Books have no place in her life. “I can’t waste time reading a book,” she shrugged her shoulders.

Gary says of her, “The kid can act. She can step out and get four thousand a week. I’m just a type.”

Beneath the boisterous manner of Lupe is a canny mind. She is fully conscious of the fact that she lives in a carnival town. And if it were not such, she would make it so.

Lupe’s bedroom might serve as a DeMille motion picture set. It is black, gold, and silver. The vast low bed is undoubtedly larger than the entire floor space of some rooms which the young Mexican lady perhaps occupied during her struggle for the tinsel of success. It was in strident contrast to the living room, where the soft glow of lamps and the fresh flowers gave the effect of a play about to begin.

Cooper’s habits are those of an outdoor man.

He takes long motor trips into the desert. He always takes a small victrola along. His favorite music is the chant of cowboys. He wears gloves while driving. He is an amateur taxidermist and spends time in stuffing birds. His chief hobby is his dude ranch.

“I don’t deserve to be a star,” he says. “There are only about three– Greta Garbo, Clara Bow, and Charlie Chaplin.”

He always sits in the seat near the aisle at the theater. Other seats cramp his long legs.

He loves dogs and hates gossip.

He delights in simple things. That the name of a town in Montana was changed to Gary pleases him. His conversation always veers from Hollywood to his native state. In a more pretentious person his attitude would be considered a pose. In Cooper it is a genuine longing.

He is considered by interviewers the most colorless star in films. Neither is a talkative person. There is in him the silence of the scenes in which he spent his boyhood. A sob sister might call him the ideal American man. He is something more–a fellow with neither cunning nor deceit who can lift a glass with a man and hold his own with a girl.

So long a women must prefer ham on the screen, they cannot go far wrong with Gary Cooper. There is at least a streak of venison in him.